FAIRFIELD, Connecticut — The last time John Pai had a solo show of his sculptures in New York, it was 1997, when he was 60 years old. There are many reasons why he is not better known in the mainstream American art world, but that is not what I want to dwell on in this piece.

In fact, it was only after my visit with him in Fairfield, Connecticut, that I learned that Pai had not had a one-person exhibition in New York in more than 20 years. I also learned that the sprawling exhibition, American Abstract Artists 75th Anniversary at O.K Harris Gallery (May 21 – July 15, 2011), which included his sculpture, “In Whose Image” (2009, welded steel, 46 x 46 x 32 inches), was the last group show to display his work.

John Pai was born in Seoul, Korea, in 1937, the youngest of three children. His mother was Korean but born in Russia, from which she was forced to flee during the Russian Civil War (1917-1922), while his father, a Korean Presbyterian minister committed to helping his country gain independence from the Japanese, found asylum in the United States during World War II, leaving his family behind in Korea. When they were reunited after the war, Pai’s mother demanded that they live someplace safe for the sake of the children.

They came to the United States in 1949, but, because of the tumultuous changes taking place in Korea at the time, his parents returned there and left him in the care of an American family. When I asked Pai where in the US his family had brought him, he said Wheeling, West Virginia, which reminded me of a poem by James Wright, “In Response to a Rumor that the Oldest Whorehouse in Wheeling, West Virginia Has Been Condemned,” which contains these lines:

For the river at Wheeling, West Virginia,

Has only two shores:

The one in hell, the other

In Bridgeport, Ohio.

After I told Pai that the only thing I knew about Wheeling was a poem, I decided it would be prudent not to pursue this line of conversation any further.

As the day passed, and I learned more about Pai’s life and work, it became clear to me that there is a strong need for a comprehensive monograph, which, for obvious reasons, should be published in both English and Korean. While Pai shows regularly in Korea, and has been the subject of museum exhibitions there, he has lived in the US for 70 years, and, for much of that time, he has been involved with Pratt Institute.

After living in West Virginia, Ohio, and New Jersey, Pai received a full scholarship to Pratt and moved to New York in 1958. In 1962, he received a Bachelor of Industrial Design. After traveling in Europe and looking at art, he went back to Pratt and earned an MFA in sculpture, which he received in 1964.

Around this time, he also began teaching at Pratt as well as the Parsons School of Design. In 1965, he became chair of Pratt’s undergraduate sculpture program, which meant that he was given the task of building the department, which he did.

Wanting to devote more time his own work, he resigned the directorship in 1974 but continued to teach until he retired in 2000. Taken together, his involvement with Pratt — as a student, faculty member, director, and administrator amounted to more than 40 years.

Pai first came into his own in the 1960s, and a number of things stick out about what he was doing at that time. He seems to have known every Korean artist in town, especially Kim Whanki (1913-1974), who lived in New York from 1963 until his death, and Kim Tschang-yeul (1929), who was there from 1966 to ’69.

Although he was younger than both of these artists, his steady teaching job and financial stability meant that he was able to host, as he told me, “parties for Korean artists, musicians, and writers, along with some Korean students” in the house that he shared with his wife, Eunsook, and their two children, in Brooklyn. One attendee was Nam June Paik, who played popular Korean songs on the piano. They never talked about art. Other friends during this period included the sculptor Han Yongjin and his wife, the painter Moon Mie, the painter Po Kim, and the pianist Kun-Woo Paik.

This was Pai’s community, which existed apart from the mainstream, predominantly white, art world. It seems to me that this coterie of artists, who knew each other at a crucial point in their careers, has never been acknowledged as an important force in New York. It is also worth noting that — on a global scale — a number of Korean painters, many of whom were born between the late 1920s and early 1930s, began to rise to prominence at that time, often by showing their work outside of Korea: Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-keun, and others.

In 1959, Pai saw the New Images of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (September 30–November 29, 1959, curated by Peter Selz), and afterward contacted one of its participants, the sculptor Theodore Roszak (1907-1981). He began working as his assistant in 1960, while still an undergraduate, and remembers helping with Roszak’s show at New York’s Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1962.

Writing in an email, Pai remembers Roszak as “very patient and caring.” His time with Roszak accelerated his education, especially with materials. When I pointed to a small sculpture on a shelf that resembled an abstract version of a prehistoric bird, Pai said it was done around the time that he was Roszak’s assistant.

In 1963, in response to his experiences with Roszak, he developed a way of making art that has characterized his work ever since. This is how he put it to me after I asked him when he decided to work solely with thin steel rods, which may or may not be copper coated, stating in an email:

I wanted to reduce the amount of tooling & machining and simplify the process so that it would be more like drawing in space. Reducing the size of the basic unit gave me a lot of freedom.

When I mentioned Ruth Asawa and her use of metal wire and a weaving-like process, Pai said that he did not want his work to be flexible nor did he want it to hang from the ceiling. He wanted his sculpture to maintain its form.

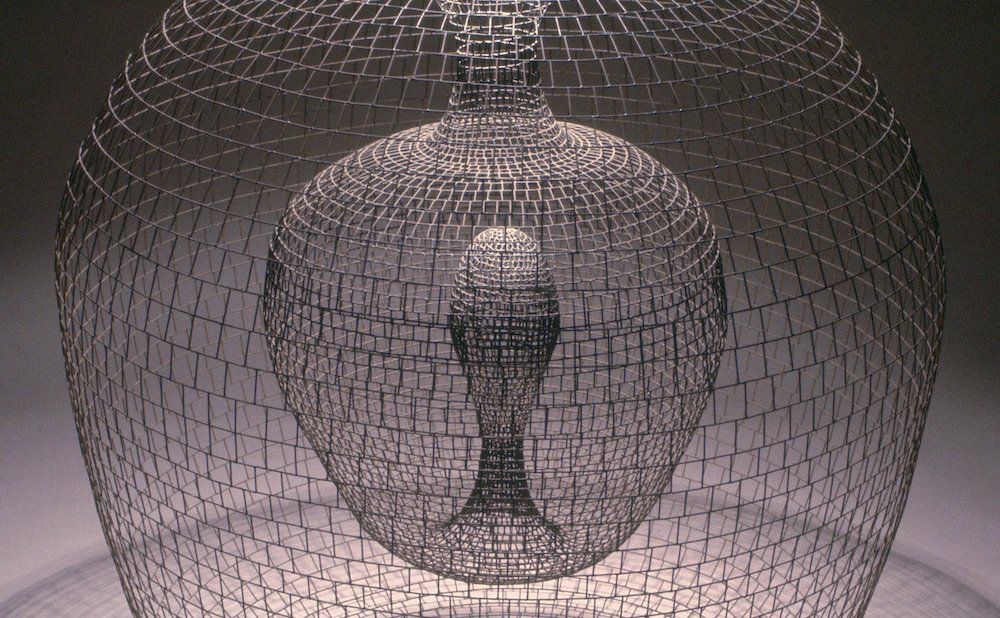

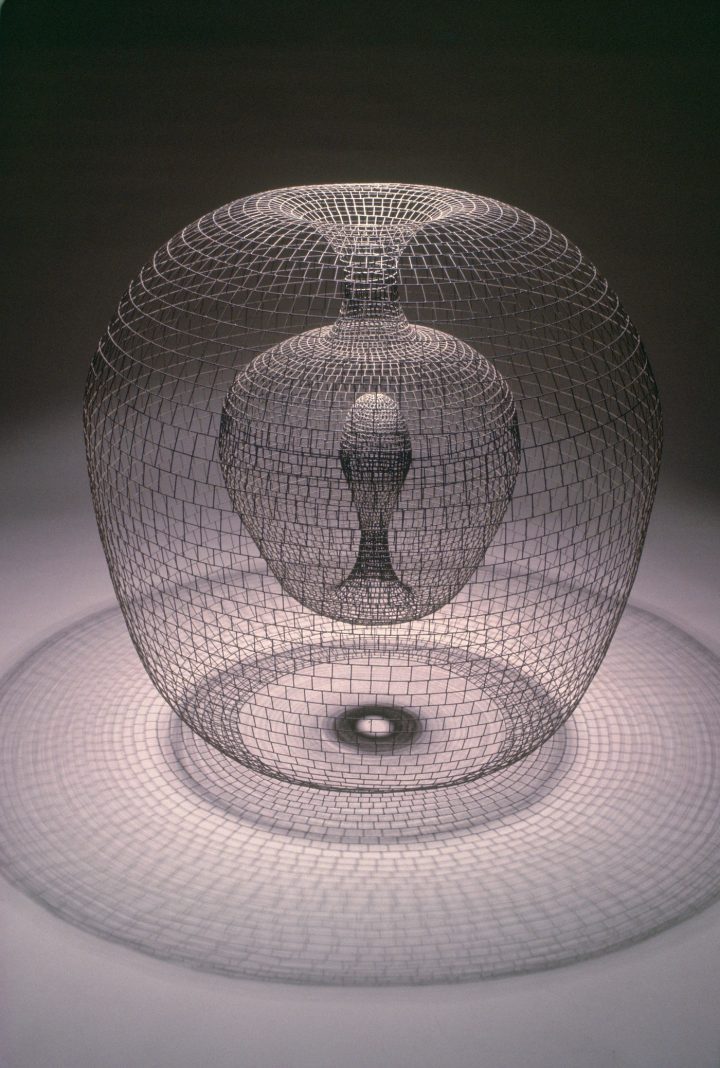

Pai’s process is slow and incremental, literally one line at a time. Many of his pieces consist of open grids made of thin steel rods welded together. The grids seem capable of attaining any contortion, torque, or change in size. A number of open, self-contained, freestanding works are composed of a form inside a form inside a form, all made from the same bending, folding, curving plane. The only equivalents I can think of are three-dimensional computer graphics, perhaps theoretical models of a black hole or an imploding galaxy.

One of the writers that Pai was reading while making such early works as “Involution” (1974) and “Convolution” (1976) was Guy Murchie, author of many books on science, including Music of the Spheres: The Material Universe from Atom to Quasar, Simply Explained; VOLUME I, The Macrocosm: Planets, Stars, Galaxies, Cosmology, which was first published in 1967.

Pai has also studied music and can play a number of instruments (piano, saxophone, clarinet, and cello), and he believes that his interest in structure has helped inform his interest in various branches of science, including physics and biology. Given his early intention to study architecture, it seems to me that he has expanded his interest in visible structures to include invisible and theoretical ones.

In more recent works, such as “Pulse” (2008, welded steel, 53 x 48 x 22 inches), an open, gridded, two-sided, three-dimensional plane of varying widths seems to collapse together near the center. Something similar happens in “Atom’s Rib” (2010, welded steel, 70 x 66 x 32 inches), where the rectilinear, gridded planes whorl and narrow as they move toward the center, becoming a vortex of wires, as if some unspecified force had passed through them.

Pai’s sculptures are not static. His work seems to be undergoing change; in some cases, it is like a three-dimensional record of a state of transformation. Terms such as decay and entropy – which we associate with Robert Smithson – come to mind while looking at Pai’s work. We see his forms as well as see through them. They feel solid and vulnerable.

Made of the simplest, most pared-down means — cut, bent, and welded steel rods — Pay has achieved a remarkable fluidity. They are meticulous drawings in space, but they are also much more than that. They are meditations on inescapable change and disruption, topographical models of unseen forces.

This content was originally published here.